HISTORY

OF THE DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCE By

Arthur Gibbs Sylvester, Professor Emeritus, Geological Science Modified 24 Febdruary 2020

The

Riviera Years – 1938 to 1954

The Earth Science department formed as an instructional and research

unit in 1960 but initially was known as the Department of Geology, later

Geological Sciences, and now Earth Science. Much earlier, however, in 1938 when Santa Barbara was part of

the California State College system and located on Santa Barbara's "Riviera",

the "department" had its beginning with a young chemistry

professor, Ernest L. Bickerdike, who offered the first course in geology. He had minored in geology while an undergraduate student at USC.

Charles Douglas Woodhouse was appointed as the first professor of geology

in 1939. He had recently

retired as superintendent of the Champion Sparkplug Mine near Bishop in Mono County, and although he had two law degrees, one from Columbia and the other from Boalt Hall at the University of California, his true interests were mineralogy and mining, he volunteered to teach a slate of several geology courses at UCSB. Before taking up his duties at the Champion Mine, he spent a year at the University of Paris, France, studying mineralogy.

UCSB accepted his offer and by 1947 he regularly offered courses in physical and

historical geology, mineralogy, and gemology.

His program ultimately led to a major in geology in 1954.

Santa Barbara State College transferred to a reluctant University of

California system in 1944, thanks to the persistent efforts of Santa

Barbarans Tom Storke and Dwight Murphy. Woodhouse served as the Dean

of Men and Veterans Coordinator at the college and so became acquainted

with Robert W. Webb of UCLA, the University-wide coordinator of Veterans

Affairs. Webb saw the possibility of establishing and shaping a new geology

program at Santa Barbara in a University of California setting.

His vision and relationship with Woodhouse led to his transfer

to Santa Barbara from UCLA in fall 1948.

Woodhouse's courses had generated considerable interest and enthusiasm for geology among the students, as evinced by rising class enrollments, and by Woodhouse's popular field trips open to any interested students. Webb knew from his experience at UCLA that these field trips were effective in generating and sustaining student interest in geology. Webb's arrival allowed the curriculum to expand and include the first two years of a major plus some additional upper division offerings. Webb and the Department of Physical Science obtained tentative approval for an addition position in geology. Webb nominated three candidates he had known at UCLA. All were close to completing the PhD degree: Warren B. Hamilton, John T. McGill, and Robert M. Norris. All came to Santa Barbara to be interviewed by Woodhouse, the Department, and the Provost of the College, J. Harold Williams. Webb did not participate in these interviews. Norris was told he'd be offered an appointment if the University would authorize it.

By 1951, everything was in place to expand the geology faculty to three, but Norris' appointment was deferred owing to the sharp post-War drop in enrollment that followed the graduation of most returning WWII veterans. He was assured by the Department of Physical Science that it still wanted him if he could come in July 1952, but fortunately for Norris, his supervising professor at Scripps Institution had just received a research grant from the American Petroleum Institute to begin a study of Gulf Coast sedimentation at two localities, one in the lower Mississippi Delta, and the other on the south Texas coast near Corpus Christi. Norris was appointed Field Party chief for the Texas part of the study and embarked on what today is known as a "Post Doc", a term not much used in 1951.

Enrollment remained low in 1952, but Webb went on sabbatical

leave that year to serve as Executive Director of the newly formed American

Geological Institute in Washington, D.C. Thus Robert M. Norris, who

had expected to join the faculty in 1951, was employed as a one-year

sabbatical leave replacement for Webb, arriving on the campus in late

June 1952 after his stint in Texas.

By 1953, student enrollment in geology courses had increased strongly even though campus enrollment did not. In those days all members of the Physical Science Department were expected to teach labs in a service course for Elementary Teaching majors - Physical Science 1A-1B. Lacking graduate students on campus for such duties, teaching loads were quite heavy by present University practice. Webb and Norris, for example, taught several times introductory physical geography, another required service course for Education majors. These responsibilities certainly reduced available time for research, but it was a transitional time between the State College and the greater emphasis on research characteristic of the University of California.

The

Pre-Major Years – 1954-1959

Prior to 1954, the University was known as Santa Barbara College and occupied two sites in Santa Barbara: the main or Riviera campus on the hill above the Old Mission, and the Mesa campus where Santa Barbara City College is now located. The State College planned to move its entire operation to the Mesa site, but had transferred only one department, Industrial Arts, by the time the University of California took over the school. The University decided that the 80 or so acres at the Mesa was too small for the future needs, and so in 1954 it acquired from the War Assets Administration the abandoned Marine Corps Air Base at Goleta Point where the present campus is now located.

Two permanent buildings had been completed on the Goleta

Mesa campus, as it was known then, by the fall of 1954: The central unit of the main library and

the Science Building that housed all natural sciences, including geology,

which was assigned two offices and one laboratory. All other campus buildings were refurbished military buildings.

Webb was chairman of the Department of Physical Science, which then

included chemistry, physics, and geology.

Woodhouse retired in 1955 and was replaced by Richard V. Fisher, a new PhD, from the University of Washington.

Junior major classes were added with the move to the new campus

in 1954, and senior classes were put in place with Fisher's arrival in 1958.

With the arrival of Fisher, the three geologists made plans to offer a geology major beginning in the Fall semester of 1956 in expectation that faculty covering such specialities as paleontology and structural geology would be added by the time the first majors were ready to graduate. This plan worked out for the most part with temporary appointments, including Robert Roach, a "hard rock" geologist trained at the University of Cardiff in Wales, but a few of the early graduates had to take missed basic courses as graduate students at other institutions.

The first graduating class was that of 1956.

Because of the small number of majors, about five or six, UCSB

students had to complete summer field geology at another UC campus. During the first year or two, most went

to UC Berkeley's summer field geology camp then taught by the redoubtable

Nicholas "Tucky" L.

Taliaferro.

It wasn't possible to offer a course in paleontology to the majors

between 1955 and 1959 because of the heavy course loads carried by the

3-man faculty. The students had to take that course at

the graduate level if and when they continued for a higher degree at

another institution, but the enrollment and number of majors had grown

sufficiently by the fall of 1959 that the administration authorized

another appointment in geology.

Donald W. Weaver, who had nearly completed his PhD at UC Berkeley,

filled that position. His arrival in January 1959 filled out the major by providing

the first course in invertebrate paleontology and, by 1960, the first

UCSB summer field course.

The

Growth Years – 1960 to 1980

In the years just preceding 1960, Webb, as Chairman of the Physical

Sciences, had been working assiduously with the administration to split

the department into three separate departments:

physics, chemistry, and geology.

Beginning about 1957 or 1958, each of the three groups had become

increasingly autonomous under separate vice chairmen, so in 1960 the

split occurred quite smoothly.

The first chairman of the new Department of Geology was Robert

M. Norris, and as the program continued to grow, he was able to hire

William S. Wise in 1960 as the fifth member of the faculty.

Wise offered advanced mineralogy, hard-rock petrology, and eventually

even summer field geology.

UCSB's enrollment grew rapidly in the 1960s, and the administration's

commitment to the transformation of the campus into a strong, general

campus of a research university allowed appointment of scholars of some

standing to the faculty. As

a consequence of this move, graduate study leading to the Masters degree

in geology was authorized in 1963 following the appointment of senior

scholar Aaron C. Waters, who had many years of distinguished teaching

and research at Stanford and Johns Hopkins universities.

His appointment clearly set geology at Santa Barbara on its way

to national prominence and stature, and he was able to attract two other

experienced scientists to join the department:

Clifford Hopson, then a junior professor in petrology at Johns

Hopkins University, in 1964, and geochemist George R. Tilton from the

Carnegie Institution of Washington in 1965.

Waters contributed importantly to the authorization of the doctoral

degree in 1965, but he left UCSB in 1967 to develop a department of

Earth Sciences at the newly opened UC Santa Cruz campus.

Growth continued at a rapid pace at UCSB during the 1960s, and

several new faculty were appointed to the Department of Geology but

moved on to other positions after a few years.

Among them were:

Even with the addition of more faculty, the increase in the number of majors made it increasingly difficult to staff the burgeoning freshman labs. For the first few years before the graduate program had begun, the department hired such people as V. L. Vanderhoof, Director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History and Mrs. Moritmer Andron, wife of an economic professor, who had been a geology major during her college days. Another of these "outsiders" was Geoffrey Shaw, Public Information Officer of the New Zealand Geological Survey, who came on a teaching Fulbright in 1963-64. Other faculty members who servered briefly during the 1960's included Bruce Nolf, a Princeton graduate and a specialist in volcanic rocks, and Frank Kilmer, a paleontologist and stratigrapher with a UC Berkeley degree.

During these high growth years, Biological Sciences moved from

the Physical Sciences building in 1963, Chemistry followed in 1966,

and finally Physics received its own building in 1969 and relinquished

the present building, now Webb Hall, to Geology, which had just grown

sufficiently to occupy the entire building.

By 1966 geology at UCSB had become a well-known and mature department

and thus was able to attract John C. Crowell, a senior faculty member

at UCLA. Crowell, internationally known for his

studies of the San Andreas fault, made important contributions to the

department's graduate program and attracted many outstanding graduate

students that brought increased visibility and prestige to UCSB. Don

Runnells was added for geochemistry in 1967, and Arthur G. Sylvester

(structural and metamorphic petrology) was hired from the Shell Development

Company in 1967 to fill Waters' vacated slot.

Yet a third senior faculty member from UCLA, Preston Cloud, joined

the department in 1969. He

quickly established UCSB as a center for the study of pre-Phanerozoic

life and history. Cloud, already a member of the National

Academy of Sciences when he arrived, gave the department still another

prestige boost. The Cloud Laboratory, originally a clean lab to receive Lunar samples in the search for traces of organic material, was dedicated January 21, 1981.

The appointments of new faculty during the 1970s consisted not

just of new PhD degree holders, but of scholars of some professional

standing, because the department had demonstrated to the administration

that it was highly regarded nationally and could attract first-rate

faculty. This status was further validated by the elections of George

Tilton, John Crowell, and James W. Valentine to the National Academy

in 1977, 1981, and 1984, respectively. Among the new faculty in those years were:

The

Decade of Diversification – The 1980s

The concepts of plate tectonics revolutionized the geological sciences, but it took a decade for the Department of Geology to catch on fully. Crowell, Luyendyk, and Prothero, to be sure, were right on top of the advances in marine tectonics, but the department stepped right into the thick of things with its new hires in the 1980s. The department also sought to develop greater strength and breadth in paleontology, geochemistry, and geophysics as is evident from the names and specialties in the following list:

Although

the department expanded considerably during the1980s, that decade was also

one of retirements: Bob

Webb, Preston Cloud, George Tilton, John Crowell, Bob Norris, and Dick

Fisher. The retirements offered opportunities to bring in people in

the 1990s with fresh ideas and energy in new fields of research, as

well as to restock and strengthen traditional fields, especially paleo-oceanography

and paleontology.

The

department experienced some of its largest enrollments in the 1980s

when undergraduate majors numbered over 300 in contrast to the more

usual 100-120. Field classes

were so large that two sections of 40-50 each had to be taught by two

separate faculty. One year, required major courses, such

as structural geology, had as many as 110 students, thus necessitating

SRO for lecture hall 1100, as well as cadres of TAs for the sundry labs.

The unusually high enrollments were occasioned by the petroleum industry's

need for geologists nationwide, but that bubble burst after a few years,

just about the time geologic jobs opened up in the fields of hazards

and the environment. UCSB soon gained the statewide reputation

of graduating some of the best-trained, entry-level geologists for firms

in the consulting business.

Even

More Diversification – 1990-2010

Still more development of breadth and strength in paleontology and seismology were primary goals in the 1990s and 2000s. With such a high number of faculty members, lab space in Webb Hall was converted to faculty offices, and as is described in a later section, new teaching lab facilities were constructed in conjunction with new labs for Physics and Chemistry. Along with the arrival of the following new faculty also came new analytical equipment, necessitating creation of or remodeling old space in the Woodhouse and Cloud labs.

The high rate of retirement resumed in the 2000s with Art Sylvester

(2003), Bill Prothero (2004), Ken Macdonald (2007), Jim Kennett (2007),

Jim Boles (2008), Tanya Atwater (2008), Jim Mattinson (2009), Bruce Luyendyk (2010), and Rachel Haymon (2010) leaving

within a period of seven years of one another.

Sylvester continued to teach half of the summer field camp until

2009; most continued their pace of research without decrease in intensity.

The strong support staff of the Geology Department was led initially

by George Hughes and Bill Bushnell.

In the early days, George helped with field trips, set up summer

field camps, built cabinets for laboratories and rock collections, led

the transitions from temporary to permanent quarters, moved furniture,

renovated office space, made thin sections, machined parts and equipment

for the analytical labs, generally maintained Webb Hall, and oversaw

the conversion of the Woodhouse Lab and the construction of the Cloud

Lab. Bill Bushnell, with

UCSB BA degrees in both geology and biology, was George's capable assistant

in all these activities.

During the 1970s Dave Doerner was the department's museum scientist,

who curated laboratory rock and paleontologic specimens,

prepared exhibits, and supervised the department's photography laboratory.

Dave Jorgenson, Gil Williams, and Bahman Soleimani-Noori made thin sections; Steve Sutter made thin sections and helped with field trips in the 1980s; Dave Crouch was the department's

draftsman, illustrator, and master caricaturist. Mark Stein was in charge of the operation

and maintenance of the electronic analytical equipment aside from the

mass spectrometers, which Dave Pierce oversaw for many years.

Frank Daniel was succeeded by Pearl Lignon in the department's storeroom. After some years, Craig Welsh ran the storeroom until it was phased out.

Ultimately these people retired or moved on and were replaced

by a cadre of equally capable personnel, including Joe Cisneros who

succeeded Bill Bushnell as Shop Manager. Tim Cuellar became his assistant

in 2002. Dave Robbins set up the department's computer

system, network, and computer labs, later with Caesar Lozano. Yann Ricard converted the labs into a full teaching facility

and then joined his father in archeological research. Bob Dunn, who retired in 1991, was Mike Fuller's principal

assistant in the paleomagnetism lab for many years. Research associates Doug Wilson and Karen Thompson worked closely

with Ken Macdonald and Jim Kennett, respectively. Howard Berg succeeded Mark Stein and supervised

the electronic operations in the department's increasingly complex and

sophisticated electronics laboratories with aid from Gareth Seward and

Andrew Kylander-Clark. In the 1990s, Chuck Anderson was the collections curator, helped

with field trips, and established a GeoWall capability for the department.

Rick Martz took over some of these duties when Chuck moved to

a similar position Penn State University, taking Susie Leska with him.

Ruth Henry was the department secretary from 1944 to 1955. She was succeeded by Doreen Hayball and Holly Guthrie, and

later by Meryl Wieder.

The position of head administrative assistant, or Management

Services Officer (MSO) as the position came to be known, has been very

stable over the department's history.

The first was Fran Cloud who labored in a tiny cubicle office

for many years. Her successor was Meryl Wieder, followed by Priscilla

Mori, who supervised the redesign of the entire office complex and,

in the process, created a much larger office for herself and the rest

of the staff. Priscilla

went on to become the campus ombudsperson and was succeeded as department

MSO by Leslie Edgerton who retired in 2009 after more than 40 years

of service to the University. Giulia Brofferio became department MSO in 2009 following 10

years as MSO for the Institute for Crustal Studies. Frank Daniel, Anne Elwell, and Tracy Daggett were the department's

financial managers over the years, keeping close tabs especially on

research grant spending before much of that activity transferred to

the Institute for Crustal Studies in the 1990s.

The department eventually became so large and complex

that the MSO needed help, especially with personnel matters. Thus the position of Analyst and Office Manager was created

and filled ably in the 1990s and 2000s by Lou Anne Palius, N.J. Kittle,

Terri Dunson, and Renee Meuret.

The department has enjoyed a strong reputation for counseling

its students. That reputation derived largely because of the active

involvement of its ladder faculty, first Bob Webb and Bob Norris, then

Sylvester and Atwater. Eventually the student enrollment rose to such a number that the faculty advisors needed help with all the paperwork. Undergrad advisors' assistants were Patty Kelly,

Lori Okamura, Scott Anderson (1993-1994), Robin Hagle (2000-2001), Christine

Choi, Christian Malles, Tammy Karin, Hannah Ocampo, and Sean

O'Shea.

Grad assistants have been Evelyn Gordon, Leslie-Anne Fredrickson, Craig Welsh, Susie Leska, Sam Rifkin, and Hannah Ocampo.

PHYSICAL

PLANT

Prior to 1900, several thousand native oak trees covered the

present UCSB campus mesa. They were gradually cut down for firewood

and steam locomotive fuel. Then to make room for bean fields, the

land was cleared of additional trees and stumps, and long rows of eucalyptus

trees were planted as wind breaks.

Some of the rows of trees are still extant in 2010.

When World War II broke out, the military acquired the mesa and

the adjacent Santa Barbara airport to develop a training base for Marine

air pilots. At the end of the war, the military sold

the mesa site with all its buildings and facilities to the State of

California for $1. Thomas

A Storke, Dwight Murphy, and other influential Santa Barbarans lobbied

strongly to convert the site into the eighth campus of the University

of California.

The master plan that President Clark Kerr developed for the University

visualized the UCSB campus as the University's "liberal arts"

campus with enrollment to be capped at 8,000 students, although the

local faculty argued for a limit of 3500 and aimed for an "Amherst

of the West." The first permanent buildings were the

main central Library and the Physical Sciences building. Geology had two offices and a laboratory

in the building that also housed Chemistry, Physics, and Biology.

All the rest of departmental functions, including geology faculty

offices, labs, and some lectures, were located in the temporary buildings

left by the Marines.

Campus building construction proceeded at a leisurely pace and

produced the pink brick, two-story dormitories, Girvetz Hall, and the

Arts and Music building. Noble

Hall was among the new buildings and took the biologists out of the

Physical Sciences building. Then on October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union

sent Sputnik 1 into orbit. It was the first artificial satellite

in history; only a month later, however, the even larger and heavier

satellite, Sputnik 2, carried the dog Laika into orbit.

The Sputnik launches came as a shocking surprise to the United

States. The space age had dawned and America's Cold War rival suddenly

appeared technologically superior.

To combat this threatening menace, the U.S. poured great sums

of money into higher education to develop science that would put us

ahead of the Russians. Big money became available for new, multi-story

Physics and Chemistry buildings in 1960, and once they were finished,

Physics and Chemistry vacated the Physical Sciences building in 1969;

Geology was able to fill in the empty space and expand. The department's consolidation, from the

temporary buildings to the Physical Sciences building, now Webb Hall,

was largely completed by 1970.

Another of the early pink brick buildings was the "Rad Lab"

– the Central Laboratory for Radioactive Materials (CRLM) –

where studies of low-level radioactive materials took place. Once the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty went into effect, however,

great student and community pressure forced the UCSB administration

to disband the facility. Once

it was vacated and cleaned, the Geology Department was standing first

in line to take over the building for quantitative research labs, especially

mass spectrometry. Only a few years elapsed before the building

was named in honor of the campus' first geology instructor, Charles

D. Woodhouse.

U.S. science made good on its promise to overtake the Russians

in space when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the Moon on July

20, 1969. Moon rocks that that Astronauts brought

back to Earth needed study, and for that purpose, the Preston Cloud

lab was built to receive and study not only those rocks for the presence

of organic substances, but also terrestrial rocks for pre-Phanerozoic

life.

As the Geology faculty increased in number and research sophistication,

the demand for lab space escalated so much that teaching lab and classroom

space in the Physical Sciences Building was converted to labs and faculty

offices. Graduate student office space was found

in the "motel wing" of Noble Hall as well as in "temporary"

buildings, such as the "grad shack", that are becoming increasingly

permanent over the years.

The space crunch was felt also by Physics and Chemistry, who

struck a deal with Geology to give Geology the top floor of a new Physical

Sciences building in trade for its support for the bulk of the proposed

building going to them. The ploy worked, so in 1994 Geology moved

into a spacious modern teaching lab space in Physical Sciences Building

II (affectionately known as PSBII).

The drawback was that the geosciences labs and students were

no longer "among us" but are now spatially separated from

Webb Hall by the Physics Building.

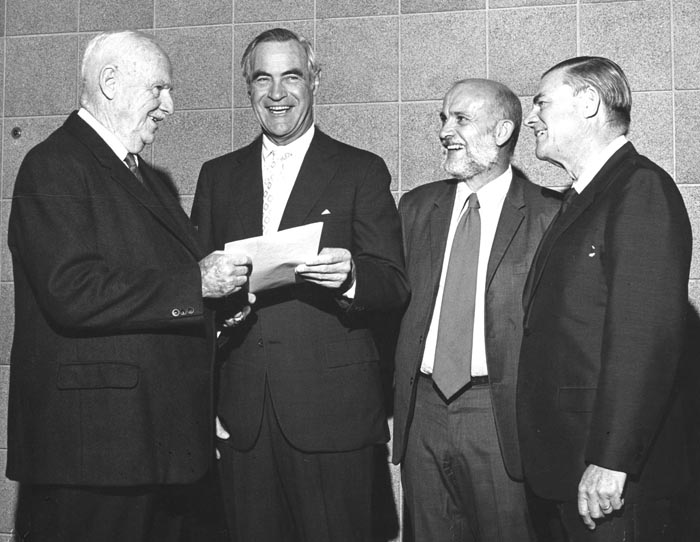

The "old" Physical Sciences Building (PSB I) was renamed in honor of Robert W. Webb and dedicated on 2 April 1995, with Bob's family in attendence.

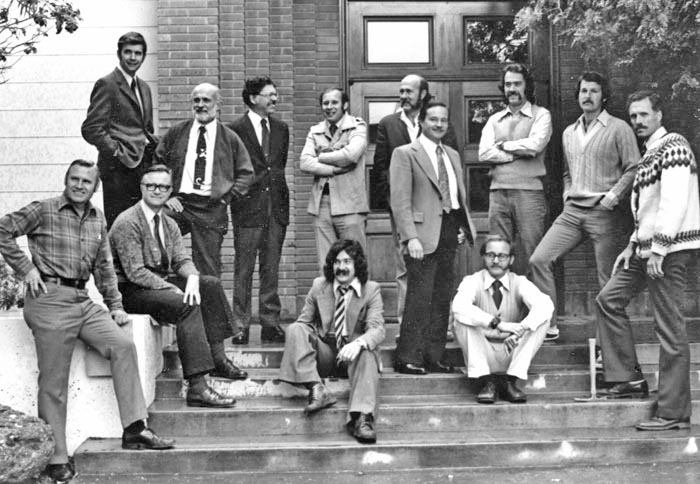

SUMMER FIELD CAMP The founding fathers of UCSB geological sciences, Robert Webb, Robert Norris, Dick Fisher, and Don Weaver, determined that they would not seek administrative permission to start a graduate program until the undergraduate program was competitive with the best in the state. In 1961, department chairman Bob Norris, called "snarling Charlie" Gilbert at Berkeley to see if UCB would take three or four of our majors for summer field camp. Gilbert said, "OK but the UCSB students would have to take Berkeley's preparatory field course first." Norris protested vigorously, pointed out that the UCSB students had had two semesters of field courses, and he reminded Gilbert that UCSB is a UC campus. Gilbert relented, and then Norris told our students that Berkeley didn't think much of them. The upshot was that one of the UCSB students, Ed Green, was the best student in the summer field class, and Gilbert, to his credit, called Norris that fall to say that Berkeley would be glad to have UCSB students in the future. Accordingly in 1962, UCSB sent five students to a summer field camp in the White Mountains (Poleta Folds) consisting jointly of UC Berkeley and UCLA. Instructors were Charles Gilbert (UCB), Jack Evernden (UCB), and Don Weaver (UCSB). When the dust had settled at the end of the six-week camp, four of the UCSB students were among the top five of all 30 students in the camp, and the UCSB graduate program became a reality shortly afterward. Don Weaver together with Bruce Nolf established UCSB's first independent Summer Field Course in the Poleta Folds of the White Mountains in eastern California in 1963. George Hughes established the camp with tents and solar heated water for showers. We even had our own camp cook. UCLA and others were in the area and were all very competitive. Weaver and Nolf conducted both halves of the camp on Santa Cruz Island in 1964 and ’65. Bruce handled the volcanic north side of the Island and Don the south side. The student-faculty studies on the islands were published in 1969 by the Pacific Section of the AAPG, entitled "Geology of the Northern Channel Islands". The island field camp station was made possible and permanent through the generous cooperation of the island owner, the late Dr Carey Stanton, and the logistical support of the US Navy and its personnel stationed on the island. George Hughes was able to procure the old instrument landing building at the LAX and used it to replace the tents. Subsequently and with the support of the University Regents, Santa Cruz Island Field Station became part of the University’s Field Reserve Reseach Facilities. Weaver served as its Director for a number of years. He continued to teach the summer field course at different times for a total of nine years. In the iterim, Dick Fisher took the class to the famous vertebrate fossil beds of the John Day Formation in eastern Oregon for a period of eight weeks. It soon became clear that eight weeks was too long a time and it reverted to six weeks. For three years in the late 1960's Bill Wise and Eldridge Moores taught a combined UCSB and UC Davis Summer Field course in the northernmost Sierra Nevada, using a US Forest Service work camp at Lake Almanor. These camps were the first in the UC system that encouraged the women students to attend. In 1974 the class was taught by RV Fisher, ably assisted by Bruce Crowe and John Dillon. The first camp was at Cedar Flat in the White Mountains, with mapping at Poleta and the west side of the Birch Creek pluton. The second camp was at the Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory (SNARL), and the class mapped in the Mt. Morrison roof pendant in the Sierra Nevada. In 1976 Art Sylvester and Chris Buckley (Cal State – Fullerton) took the camp back to the White-Inyo Range for three summers. Students would map the Poleta Folds for the first four weeks and then scatter to map areas of their choosing in the White Mountains for the remaining four weeks. A highlight each year at the end of the Poleta Fold mapping was the opportunity to fly over the Poleta Folds in Chris' Cessna 182.

George Hughes and Bill Bushnell built infrastructure for a base camp to serve the Poleta Folds mapping in a pinyon and juniper forest at Cedar Flat at 7200' at the crest of the White Mountains. Students lived in private tents just as they do today. In 1984, ARCO Oil & Gas, through the instigation of alumnus Doug Hastings, gave funds to the department to acquire a splendid kitchen trailer that was used for nearly 20 years. The camp was reduced to six weeks duration in the early 1980s and then divided into two halves, each taught by a different instructor or sets of instructors. In 1982 and 1983 the enrollments exceeded 100 students, so that the camp had to be run in two consecutive four-week sessions at Poleta in 1982. But in 1983 the course was taught in two overlapping sessions with identical course contents but with separate pairs of instructors. Each group worked initially in the Poleta Folds for three weeks before going into binary fission. One of the sub-sections so formed went to Santa Cruz Island with Jim Boles and Steve Lipshie (UCLA), while the other went "walkabout" in the greater Poleta Folds region with Rick Sibson and Cathy Busby. The subsections then interchanged for the next 10 days before recombining at UCSB for preparation of final reports. Assignment to each of the groups was by lottery. Individual preferences were accommodated only if an especially strong case (job offer, etc.) could be made. Swapping between groups by mutual agreement was OK prior to the start of camp. Enrollments decreased somewhat in 1985 and 1986 to around 70, still engendering enormous staffing and logistical problems.

The general plan evolved over the years into one wherein the first three weeks emphasized mapping principles and mechanics, and the second allowed students more latitude to practice their skills in an area having rocks and structures different from those in the first three weeks, and where the students had more individual responsibility for the area they mapped. Some areas were chosen for the second half camp that had never been mapped or had not been mapped in 100 years. The students' mapping in one of those areas north of Lake Tahoe was compiled into a regional map that was published by the US Geological Survey. The main mapping area over the years for the first half of camp has been the Poleta Folds, in Deep Spring Valley on the east flank of the White Mountains in eastern California. It comprises Lower Cambrian miogeoclinal strata, wonderfully folded into anticlines and synclines at all scales, and all cut by major and minor faults. It is such a marvelous and popular place for students to learn and gain confidence in doing what geologists do that as many as 14 separate geology departments may map there in a single year. Critics complain that such heavy use results in well-worn trails along all the contacts and to the critical outcrops, but proponents counter that each student is still responsible for making a map of the rocks, not the trails. UCSB students mapped at Poleta almost every summer from 1976 to 2003 when it seemed likely that 2003 would be the last summer there, because Caltech's Jet Propulsion Laboratory took an indefinite long-term lease on Cedar Flat campsite for a deep space listening facility (CARMA). A complex of 12 giant radio telescopes now occupies much of Cedar Flat, and all the campsites previously used by geology departments to access the Poleta Folds have been phased out or obliterated completely. In summer 2004, therefore, the UCSB students went to northern Nevada with Phil Gans for the first half of the camp. Jim Boles took the students to Santa Cruz Island in 2005 and 2006; Cathy Busby took them back to the Poleta Folds in 2007 but stayed at White Mountain Research Station at Crooked Creek. Then Art Sylvester returned the camp to Cedar Flat in 2008 and 2009 after the US Forest Service and JPL built three nice, new group camp sites on the west side of the flat. Bill Wise and Art Sylvester took the second half of summer field camp to north Lake Tahoe in 1987 and approximately every other year thereafter, and thereby began two decades of systematic mapping of all or parts of thirteen 7.5' quadrangles leading to a digital geologic map of nearly 300 square miles of country previously mapped in 1895 Waldemar Lindgren at a scale of 1:125,000. Nearly 100 students participated in that mapping over the years. Base camp in 1987 for the first Tahoe mapping was the Sagehen Creek Field Station located about 10 miles north of Truckee, whereas subsequent camps until 2007 were housed in the University's ski lodge at Norden near the crest of Donner Pass. It returned to Sagehen Creek Field Station in 2006 and 2007. More than 1000 UCSB students have participated in summer field camp over 40 years. The instructors have included Don Weaver, Dick Fisher, Jim Boles, Jim Mattinson, Phil Gans, Rick Sibson, Cathy Busby, Bill Wise, and Art Sylvester with a robust cast of graduate student TAs. Field study sites have been in eastern California, northern Nevada, Santa Cruz Island, and various sites in the northern Sierra Nevada that include Lake Almanor, Frenchman Reservoir, Sierra Buttes, and the northern Lake Tahoe region.

GEOLOGY

18

In the early days the Department of Geology had a "department

field trip", offered twice each year, open to any and all students. Even graduate students, staff, and community

friends were welcome. Some

of the faculty brought along their children to be "trash trolls".

Bobs Webb and Norris were the usual leaders with essential assistance

from George Hughes and Dave Doerner, later from Bill Bushnell, Joe Cisneros,

Chuck Anderson, and Tim Cuellar.

The trips lasted four to four and a half days, leaving campus

on Wednesday noon or Thursday morning and returning on Sunday evening.

Regrettably the administration began to count beans in the late

1970s and wonder if the faculty ever worked on this campus.

Yes, the geology department faculty worked even on weekends and

holidays taking students on enrichment trips in the field where geology

is, but with nothing on paper to show for those efforts aside from gasoline

receipts. So in 1980 the department created a one-unit

Geology 18 course for students who went on the trip, and ever after

the "departmental trip" has been known as Geo 18.

The trips have been exceedingly popular among students through

the years and have been instrumental in attracting new students into

the major. The stories from those early days are

legion and legend, especially concerning adventures with an old school

bus that George Hughes would drive into some of the remotest and inaccessible

corners of the Mojave Desert.

Bob Webb's searches for old cars and car parts on the Mojave

Desert were the grist for many campfire stories.

The trips occurred in the fall and spring quarters and went mainly

to desert areas where the weather would probably be reasonably favorable

at those times of year. Webb

and Norris preferred campsites out on big alluvial flats where there

was little to trip over or fall into, although alternative sites would

be sought if it were a windy night. A most delightful campsite was among giant

granite boulders in the Granite Mountains of the central Mojave Desert

or in Joshua Tree National Park.

Perhaps the most popular trip among students was to Death Valley.

Because of the long driving distance, the trip left campus on Wednesday

noon and spent the first night in a camp about halfway between campus

and the valley, commonly in the Summit Range where a reasonably flat

area is down in a valley carved along the Garlock fault, and where the

wind blew only a little less than on the flat desert floor. Camping

in Death Valley itself is restricted to designated campgrounds inhabited

by lots of other people and requiring a fee, but having proper toilets.

Webb and Norris preferred to camp a few hundred meters outside the park

boundaries, such as a big flat in the Amargosa Desert near Rhyolite

ghost town, and on a flat in Greenwater Valley at the base of the road

up to Dante's View. Lacking proper toilets, Webb or Norris would point

in one direction for the men, the other for the women, and would call

attention to the abundance of scattered creosote bushes that offered

a bit of screen. A swim at Tecopa Hot Springs, or at one of the swimming

pools at Stovepipe Wells or Furnace Creek, was always a high point of

the trip.

Another popular four and a half day trip explored Owens Valley

in eastern California. This

trip was subject to occasional cold, windy, and sometimes rainy weather

that always made for high adventure. The entire camp was blown away

on two separate occasions on the flat above the Chalk Cliffs overlooking

the town of Bishop. Stops were usually made at Fossil Falls, Alabama

Hills, Owens River Gorge, and Mono Lake. On a few occasions, the Owens

Valley trip detoured eastward to Saline Valley and Eureka Valley.

One safari through Saline Valley resulted in a spate of flat

tires, necessitating a midnight run by Bill Bushnell to Bishop to fix

flats or buy new tires so that the caravan could return to Santa Barbara.

He returned to camp with the tires at 5:30 am to find the campers having

a jolly if not raucous breakfast birthday party for Bob Norris. Bill

had to make another evening run to Bishop on still another safari into

Saline Valley when bolts holding the engines to the frames were shaken

out of several of the 10 new university carryalls.

The third and shortest trip went to the central Mojave Desert.

It featured visits to the abandoned Vulcan Mine, the singing sand dunes

at Kelso, ancient Lake Afton, colorful Afton Canyon, the subterranean

Mojave River, Rainbow Basin, and the Norris family's "Bunny Club". Trilobite fossils were eagerly sought and collected in the

southern Marble Mountains near Chambliss.

The fourth trip was a lengthy safari to the Salton Sea in the

Coachella and Imperial Valleys. Favorites stops included the Mecca Hills,

Travertine Rock, Split Mountain Gorge, mud volcanoes near Wister, and

sometimes a detour home through Joshua Tree National Monument, now Park.

Tanya Atwater became involved in the trips in the 1990s and broadened

the scope of the trips to take in more of California, no matter the

weather. One memorable trip went to the San Diego

coast and mountain area. Several of her trips explored the San Andreas

fault in central California and thence out to the Big Sur coast and

south along Highway 1 to San Luis Obispo.

Ed Keller began his bi-annual spring trips to Yosemite about

the same time. Geo 18 transferred to Susannah Porter and Phil Gans after

Tanya Atwater retired.

The Geo 18 trips have been remarkably free of serious incidents. Aside from a broken clavicle suffered by a fellow doing a front flip off the crest of a sand dune, the only really serious happening was a single car accident near Garlock in the late 1950s that killed the student passenger, Jim Hamilton, when ejected out of the car driven by student Jim Cruz. Bob Norris recalls: " Webb, Norris, and Fisher offered each fall and spring voluntary, general interest field trips open to all students. These were camping trips to such areas as the eastern Sierra Nevada, the Salton Trough, the Mojave Desert, and Death Valley. Each trip was three or four days long. They were very popular with the students and an effective way to recruit new majors. When former students return to campus, moreover, they nearly always ask if the department still offers the trips. "Sometime in the late 1950's, Fisher and Norris led one of these trips to the Goldfield, Nevada, area. Woodhouse had recommended a good mineral-collecting locality at Nivloc, near Goldfield. Norris and Fisher had hoped to camp there, but no sooner than they arrived, three or four rattlesnakes were spotted and it seemed wise to find another spot. As the group was leaving, one of the drivers backed his vehicle over a rock and broke the drain plug off the gas tank. All the cooking pots were brought and used to catch as much gas as possible. "One of the students had heard that chewing gum would serve as a temporary repair. Another student had a large supply of bubble gum that was passed around so many could chew up a big wad. Once this was done, a wad of gum was stuffed in the hole in the tank. The saved gasoline was carefully poured back into the tank, and to everyone's relief, the wad held. The group drove back into Goldfield in the hope of getting a more secure repair. At that time, Goldfield was on its way to becoming a ghost town. Abut the only things that allowed it to hang on was the fact that it was the county seat of Esmeralda Caounty and that it was on US Highway 95. "Luckily the gas station had an operating garage. The proprietor was dressed in greasy bib overalls and had a cigarette hanging out of his mouth, and after looking at the problem, said he could solder a patch over the hole, but that one of the students would have to remove the tank, which was quickly done. Norris, having seen the gas torch that the garage man was going to use, suggested that the group take a walking tour of Goldfield. About half went with Fisher and the rest with Norris. The Fisher group came upon the abandoned two-story County High School whose front door was open. They discovered a piano in one of the empty rooms, and because Fisher was a good pianist,, he sat down and belted out several tunes. The Norris group in another part of town could easily hear the music and wondered if the Sheriff would arrest them for breaking into the school. Nothing happened and when everyone returned to the garage, the gas tank was patched, miraculously without explosion or fire. The tank was replaced, filled with gas, the bill paid, and everyone was soon back on the road."

Chronologic

Overview

Robert W. Webb (PhD – Caltech) was asked by President Gordon

Sproul to come from UCLA, where he was Dean of Veterans Affairs, to

UCSB to help form a new campus.

Bob, known to many students and friends as RWW (Runs Without

Winding), wasn't content to establish a campus – he also wanted

to establish a distinguished department of geology.

Bob brought a fresh Scripps marine geology PhD student, Bob Norris, with him. Within a few weeks or months after settling

into his heavy, self-imposed teaching and administrative schedule, Bob

Webb had a brief cup of coffee with a UC Berkeley student, Don Weaver, who was passing through the area.

Bob hired him on the spot to teach paleontology and field geology;

faculty could be hired so informally in those days before affirmative

action.

Each of the three faculty took a hand teaching introductory geology;

Bob Webb taught mineralogy, and Bob Norris taught geomorphology and

geology of California, but before they could even think about establishing

a major, they had to hire a "rocks" person who, with Norris

and Weaver, could also teach field geology.

That "rocks" person was Richard V. Fisher (PhD –

University of Washington) who eventually became one of the world leaders

in the study of pyroclastic volcanic rocks. His work with "rocks" was supplemented with help from Bob Roach in 1959-60, Henry Aldrich in 1961-62, and Geoff Shaw in 1962-63, each of whom had one year, non-ladder faculty appointments. Increasing enrollments convinced the administration to grant the department additional ladder faculty.

Bill Wise (PhD – The

Johns Hopkins University) was then recruited as the who set up some of the first analytical equipment

for study of igneous rocks, and Joe Clark (PhD - Stanford University)

was also added to build a strong paleontologic emphasis in stratigraphy,

Tertiary paleontology and ecology.

Bob Garrison (PhD – Princeton) was added as a lecturer,

specializing in carbonate petrology and sedimentary basin analysis. Charles W. Rock was appointed as a Lecturer

in 1964. He revitalized

the elementary geology course labs and taught several lower division

courses.

Now with a strong major program in place and thriving with bright,

high-achieving students graduating with new Bachelor of Arts degrees,

it was time to think of a graduate program.

Aaron Waters (PhD – University of Washington) was recruited

in 1963 to build it and to strengthen igneous and metamorphic petrology.

He brought with him George Tilton (PhD - University of Chicago) in radioisotope

geochemistry and Clifford Hopson (PhD – The Johns Hopkins University)

in igneous and metamorphic petrology.

The PhD degree in Geology was authorized in 1964.

The 1960s was a time of departmental faculty flux. Both Waters and Garrison left the department in 1966 to establish

a new department at UC Santa Cruz, about the same time Jan Reitman joined

the UCSB faculty for geophysics.

Reitman left in 1970 to take a position in industry. Geochemist Don Runnells arrived in 1967

but moved on to the University of Colorado in 1969. John Crowell (PhD – UCLA) wanted to get out of big city

life in Los Angeles to a more serene environment in Santa Barbara, and

UCSB was happy to accept him to fill a gaping hole in structural geology. Art Sylvester (PhD – UCLA) was lured

from the petroleum industry in 1967 to add breadth in structural and

metamorphic petrology. UCLA

gave up another of its internationally renowned scientists, Preston

Cloud (PhD – Harvard University), to UCSB in 1968 for pre-Phanerozoic

biogeology and cosmology, at about the same time Keith Macdonald (PhD

– Scripps) joined the department for Phanerozoic paleoecology

but left for private industry after five years. Jim Mattinson (PhD – UCSB) was added

to bolster our strength in isotope geochemistry. Mike Fuller (PhD – Cambridge University)

came to us from the University of Pittsburgh to build a lab and curriculum

in paleomagnetism.

The revolutionary fires of plate tectonics began to blaze brightly

in the late 1960s, so the UCSB Department of Geology broadened its purview

in the 1970s by bringing in a cadre of young marine geophysicists and

geologists, thereby materially changing the tenor of the department. The first of the new additions was Dan Karig (PhD – Scripps)

who was at the forefront of some of the marine geophysical studies that

elucidated mid-ocean ridge mechanics, but he left after only a year

to take a position at Cornell University.

Karig was replaced in quick succession by marine geophysicists

Bruce Luyendyk (PhD – Scripps), Ken Macdonald (PhD – Scripps), Bill Prothero (PhD – Scripps), Tanya Atwater (PhD – Scripps)

and Rachel Haymon (PhD – Scripps).

Jim Boles (PhD – University of Otago) was lured away from

the petroleum industry to add strength in low temperature geochemistry

and sedimentary petrology. Stan

Awramik (PhD – Harvard University) was the first of several paleontologists

that the department added to build strength in that field. The department hired Conrad Gebelein (PhD – Brown University)

in 1974 for his expertise of modern carbonate tidal flat environments.

He died in 1978 in the Caribbean pursuing his studies of coral

reefs.

The 1980s was a decade of diversification, environmental awareness,

and consolidation of strength in several fields, notable paleontology

with the additions of Jim Valentine (PhD – UC Berkeley) for Cenozoic

invertebrate paleontology and Bruce Tiffney (PhD -Harvard University)

for paleobiology. Valentine moved on to UC Berkeley after

a few years. Ed Keller (PhD – Purdue University) was appointed jointly between the Geological

Sciences department and the Environmental Studies program. Rick Sibson (PhD – University of

London) spent eight productive years with us, teaching structural geology

and field courses while doing research in earthquake mechanics and fault

rocks. He returned to his

homeland, New Zealand, in 1990 to assume the chair at the University

of Otago.

In 1983 Cathy Busby (PhD – Princeton University) was hired

for her expertise in volcanic and sedimentary processes. Ralph Archuleta (PhD – Scripps) came to the department in 1984 from the U.S. Geological

Survey to bolster geophysics in earthquake seismology, followed shortly

afterward by Frank Spera (PhD, UC Berkeley), who brought strength in

experimental igneous petrology. Jim Kennett (PhD, D.Sc. - Victoria University)

came to UCSB in 1987 to head the Marine Science Institute, and with

his expertise in micropaleontology and marine geology, he fit naturally

into the department.

In

the 1990s, the department offset the retirement losses to the field

geology curriculum by adding Brian Patrick (PhD – University of

Washington), who left the department a couple years later, and Phil

Gans (PhD – Stanford University) in 1988.

It added strength to geochemistry by hiring low temperature geochemist

Michael DeNiro (PhD - ) away from UCLA, and paleoclimatologist David

Lea (PhD – University of Chicago).

Professor York Mandra of San Francisco State University taught

introductory geology and energy courses during summer session for nearly

two decades.

Geophysics

was similarly broadened and strengthened by obtaining theoretical geophysicist

Toshiro Tanimoto (PhD – UC Berkeley) from Japan. Metamorphic petrologist Brad Hacker (PhD

– UCLA) brought strength and breadth to petrology and tectonics

in 1996.

The department broadened its research scope with hydrogeologist Jordan Clark (PhD – Columbia University) in 1996. Doug Burbank (PhD – Dartmouth College) came in 2001 from USC and Penn State and succeeded Bruce Luyendyk and Ralph Archuleta as Director of the Institute for Crustal Studies. Burbank added considerable research strength in sedimentation, tectonics, neotectonics, and geomorphology. Susannah Porter (PhD – Harvard University) joined the faculty in 2003 as an expert in Precambrian paleobiology. David Valentine (PhD – UC Irvine) and Chen Ji (PhD – Caltech) came in the early 2000s: Chen Ji as an earthquake seismologist, and Valentine for marine sediment geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and geomicrobiology, and as Adjunct Associate Professor of ecology, evolution, and marine biology. Jon Cottle, Lorraine Lisiecki (PhD - Brown University), and Syee Weldeab (PhD - University of Tübingen) were appointed to the faculty in 2008. Alex Simms (PhD - Rice University) was lured from Oklahoma State University in 2009 to provide expertise in siliciclastic sedimentology/stratigraphy, Quaternary science, and coastal geology.

Several

faculty members have been honored with selection to the National

Academy of Sciences, including Aaron Waters, Preston Cloud, George Tilton,

John Crowell, Jim Valentine, Jim Kennett, Tanya Atwater, and Doug Burbank.

Waters, Cloud, and Crowell were recipients of the Geological Society

of America's Penrose Medal, the highest honor that Society can award

in recognition of outstanding original contributions or achievements

that mark a decided advance in the science of geology. The Seismological

Society of America presented its highest award, the Henry Fielding Reid

Medal, to Ralph Archuleta. Dick Fisher received the N.L. Bowen Award

of the Americal Geophysical Union (1985), its highest award for research

in volcanology, followed in 1997 by the Thorarinsson Medal, the highest

honor of the International Association of Volcanologists (IAVCEI).

Campus

Distinguished Teachers include Art Sylvester, Bruce Tiffney, and David

Lea. Sylvester and David

Valentine also garnered the Presidential Award for Excellence in Undergraduate

Research for the UCSB campus in 1995 and 2009, respectively.

DEPARTMENT

CHAIRS

Hazel W. Severy, 1946-1948

Robert W. Webb, 1953-1958, 1959, 1961-1962

E. Allen Williams, 1958-1959

Ernest L. Bikerdike, 1959-1960

Robert M. Norris, 1960-1964

Aaron C. Waters, 1964-1966

Clifford Hopson, 1966-1969

Richard V. Fisher, 1969-1973, 1979-1980, 1983-84

George R. Tilton, 1973-1977

William S. Wise, 1977-1979

Arthur G. Sylvester, 1980-1983, 1984-1986

Michael Fuller 1986-1991

James Mattinson, 1991-1994

James R. Boles, 1994-1997

Bruce Luyendyk, 1997- 2003

Jim Mattinson, 2003-2008

Ralph Archuleta, 2008-2011 Doug Burbank 2011-2014 Andy Wyss 2014 -

AWARDS

AND BENEFACTORS

•

C. Douglas Woodhouse Award (Earth Science): Awarded to a senior earth

science major for merit, scholarship, and promise of success in the

profession as determined by the faculty, in memory of C. Douglas Woodhouse,

Professor of Geological Sciences (1938-55).

• William Bushnell Memorial Scholarships (Earth Science):

Awarded to deserving geology students for Summer Field Geology. Established

by Karen Bushnell in memory of William Bushnell, former staff member

in Geological Sciences.

• Robert M. Norris Prize in Field Geology (Earth Science): Awarded to an outstanding undergraduate student in the introductory field geology course. Established by John Crowell and Arthur Sylvester in honor of Robert M. Norris, Professor Emeritus of Geological Sciences.

•

Arthur G. Sylvester Fellowships for Summer Field Geology (Earth

Science): Established in honor of Professor Emeritus Arthur G. Sylvester

and awarded to deserving undergraduate students to offset their summer

field course fees.

•

G.K. Gilbert Award (Earth Science), established by Preston Cloud,

named in honor of America's foremost geologist, and awarded annually

to the graduate student presenting the best paper based on original

research (at the regular meetings of Journal Club or Geology 260). Among

the criteria for the award, the selection committee is encouraged to

consider: Information content; clear distinction between evidence and

conclusions; quality, clarity, and relevance of illustrations; that

conclusions be reached and be clearly linked to evidence presented;

originality; grammar; response to discussion. Selection Committee shall

be composed of the Department Chair, Graduate Advisor, Instructor of

Geology 260 (Chair), a PhD Candidate, and a graduating senior. One member

shall be a woman; one shall be in, or aiming for concentration in Biogeology.

• The Lloyd and Mary Edwards Field Studies Fellowship (Earth

Science): Established by Lloyd and Mary Edwards to support annually

the field studies research of one graduate student

•

George Tunell Memorial Fellowship (Earth Science)

•

The (Rich and Eleanor) Migues Prize Field Research Prize (Earth

Science): Established by Rich and Eleanor Migues and awarded annually

to one or more graduate students whose work includes field studies.

•

Harry Glicken Memorial Graduate Fellowship (Earth Science): Established

in memory of Harry Glicken and awarded to graduate students to further

their academic

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||